What do Rust traits, React hooks, and Tailwind CSS have to do with each other? This post talks about patterns I've seen in extendable systems.

I saw this Joey Banks tweet recently:

> It's amazing how much changes when you work with a team who believes that design systems should act as the floor, not the ceiling. 🙏

and it resonated with me in a way I wasn't really expecting (because I'm not a designer). It took me a while to figure out why my brain kept coming back to it, and I finally figured it out.

Protocols

Protocols in Swift, traits in Rust, and design systems the way Joey describes them all have one thing in common — they act as floors, not ceilings. They're systems that impose soft constraints on your input, not hard constraints. They allow you to attach arbitrary behavior to objects.

In this post, I want to take this idea of expressing constraints as behaviors, convince you that its good, and show it can be applied to other systems, whether its other languages, Figma, or an operating system.

Here's a more candid breakdown:

You're in a system, and working within it

The system needs to constrain the objects you are creating

The system can either constrain you by giving you a set of low-level primitives for you to work with and compose, OR by giving you a set of "behaviors" that you make your objects conform to.

I am advocating for the latter.

What is the precise meaning of "behaviors"? I think of it as essentially being able to isolate reusable and composable ideas present across the system. Like Rust traits, as opposed to Java classes.

Here's an example:

You're creating a design system in Rust (just bear w/ me). Note that the system is the design system here, not Rust (but Rust's model makes this possible).

The design system exports its domain model as traits:

// Chaining together traits for a button

trait Button {}

trait Large {}

// Let's assume this does what we think it does

trait LargeButton: Button + Large {}

trait OpenModal {}You're creating a new login button on the main page which needs to be large and also open a modal. You'd probably do it like this:

// A struct i.e. the sepcific object you are creating

struct MainPageLoginButton;

// Declaring the trait for the struct

// Here, MainPageLoginButton acts as a *floor*. I am able to extend it

// with behavior.

impl ButtonLarge for MainPageLoginButton {};

impl OpenModal for MainPageLoginButton {

// OpenModal members //

};This may look kinda odd, but it's actually ergonomic. Adding behavior to your object requires another implementation for just that behavior; removing one is as easy.

It's actually really similar to other ideas present in web development:

React hooks

React hooks, by their own definition:

With Hooks, you can extract stateful logic from a component so it can be tested independently and reused. Hooks allow you to reuse stateful logic without changing your component hierarchy.

React hooks don't make the inheritance explicit in the same way I'm suggesting though, and its not a language-level feature, which is why you need the "Rules of Hooks" that determine the validity of their usage at runtime.

import React, { useState } from 'react';

function Example() {

// Declare a new state variable, which we'll call "count"

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

return (

<div>

<p>You clicked {count} times</p>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}>

Click me

</button>

</div>

);

}TailwindCSS

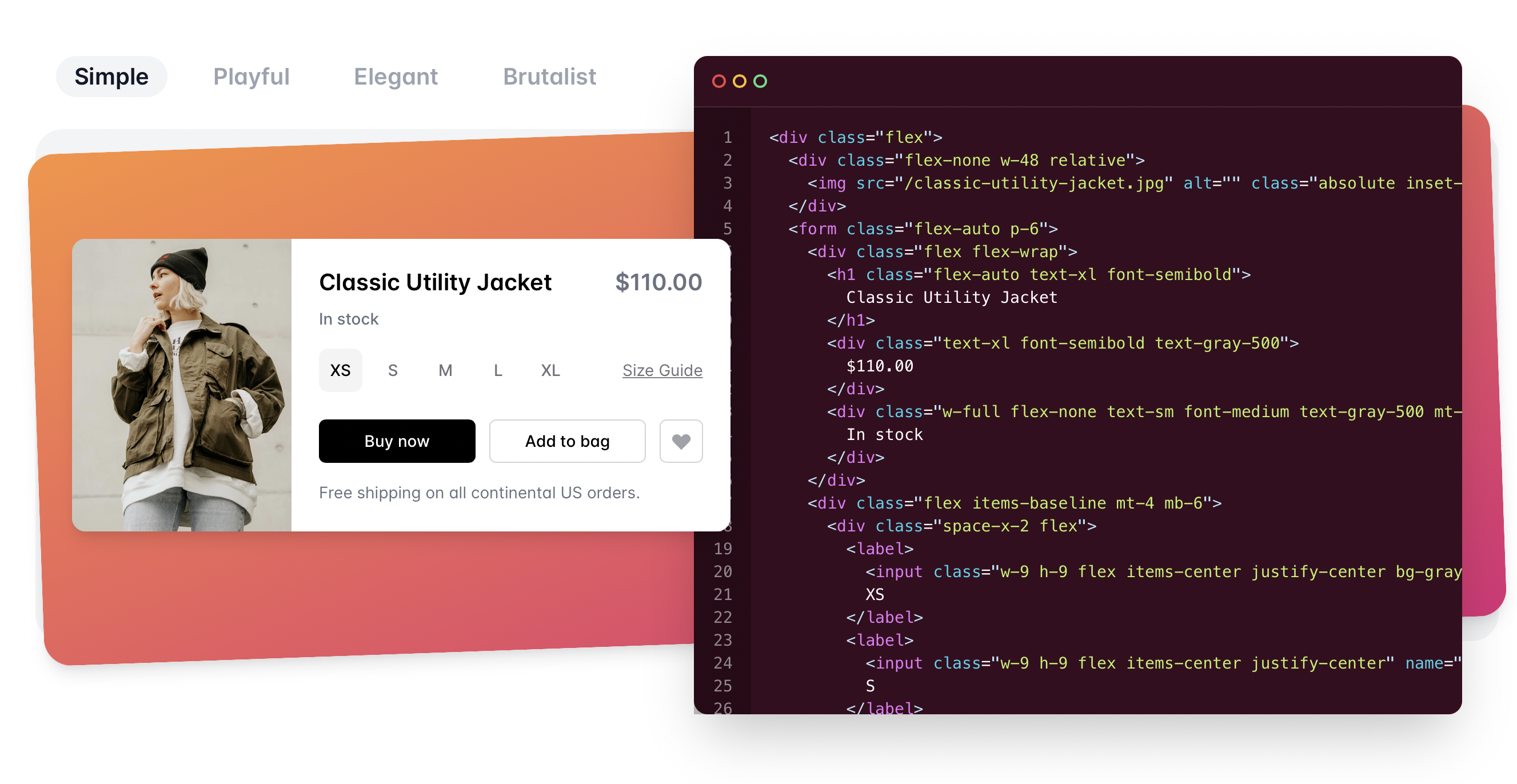

TailwindCSS is "utility-first". It's really close to the idea I presented, since seeing inheritance is easy, and inheriting, removing, is also easy. However, it's missing a core part that the protocols are not reusable or type-checked.

An example from Tailwind's website

I don't know precisely the type theory differences in these implementations, but they roughly have the same idea of inheriting behavior.

I think you'd agree w/ me on the success of this idea though! Tailwind and React hooks have really rocked both the design and web dev communities, respectively (and Rust for the embedded systems community, although that is probably more b/c of the borrow checker).

This form of protocol inheritance lets us match domains closer, and in a more ergonomic way.

Emails

Protocol-like extendability can also act as a solution for interoperability between tools. Gordon Brander has written about this a lot: https://subconscious.substack.com/p/composability-with-other-tools. If you need your piece of data to work in two separate tools, it should ideally be as simple as conforming to both of their protocols, the same way you conform to two traits in Rust.

In emails, for example, the only requirement for a message to be regarded as an email is a few headers at the top in key-value format:

From: subconscious@substack.com

To: you@example.com

CC: them@example.com

Subject: The memo format

Date: 26 Aug 21 1429 EDT

--/ Email message /--That's it. You can have extra headers, and the message itself can contain anything. This form of extendability makes it possible for other protocols or formats to exist that append extra data, such as whether it includes a display name for the sender or a BCC field, etc.

If headers did not exist, it would be necessary to invent them

I’ve been studying the history of the internet, and reading through internet RFCs to better understand the series of design decisions that lead up to our open-ended and evolvable internet. Sometimes you stumble across a flash of pure insight buried in these dusty spec documents.

Implicit vs. explicit extension

There's an important distinction between the two examples I gave, and its that emails follow implicit extension vs. Rust uses explicit extension. With emails, you create an object (a text file), and the protocols that it follows are decided implicitly from its content (could be email, could be Markdown, etc.). In Rust, the objects (structs) assume no behavior until you explicitly declare and implement them.

At first glance, implicit extension seems better: it requires less work on your part to declare the behaviors of this object. As long as you follow the format of the given protocol, you're good. But protocols can be contradictory: a different format might also need a From header that means something else than it does for the email protocol, making it impossible to inherit both.

On the other hand, explicit extension cannot be contradictory: a trait asks that a certain method be implemented, and you implement it, separate from any other trait implementations. The tradeoff here is that, of course, you need to know to code 👎🏾.

Here is a related Twitter thread where I discovered the distinction.

I'm sure its not a hard and fast rule though: maybe a protocol can allow both implicit and explicit extension or maybe there is a sweet spot between the two ideas that's fine.

Applying this idea to the operating system

The real power of this is shown when you imagine current tools that don't allow protocol-like extendability that should. Here's an example:

Figma

I keep coming back to this example. Figma components have, at least from the reaction on Twitter, shaken up the design world. Rasmus Andersson has written about the inspiration from programming concepts. But the way it is, it is mostly structurally limited. You don't "attach" a Button behavior to an object, you usually make a Button component, at which point the internals should no longer be touched. What if you took Joey Banks' words to heart and flipped the system to follow behavior-like extendability instead? I am not sure what this would look like (what does it mean to attach a "Button" behavior?), but it could be immensely helpful to designer ergonomics. If the design language and principles can be expressed as a set of behaviors, rather than a set of hard-coded components, it could get a lot easier to design and develop products.

Basically any modern-day app is structurally constrained. You enter into Notion the app, and type letters and words that get interpreted and turned into Notion symbols. These symbols and concepts, are not anything more than what they are inside Notion. I want these concepts exposed as protocols. To picture this, imagine something like this:

struct mynotes;

impl NotionNote for mynotes {

fn name(&self) -> ... {...};

fn content(&self) -> ...{...};

// Whatever else Notion may need from my notes

}

impl GoogleCalendar for mynotes {

// Whatever Google Calendar may need to interpret my notes as a calendar

// For example, maybe I keep a list of events in mynotes

fn events(&self) -> ... {...};

}Here I'm explicitly conforming my data to both a Notion note and a Google Calendar. This is the kind of extendability I want available from apps.

A big obstruction for this kind of extendability is the platform: our operating systems. If files on my system are Rust structs, there is no equivalent for Rust traits. I cannot attach behavior to my files (explicit) outside the content of the file (implicit). Moreover, files are hard to deal with! When you open a file, you are basically getting a giant array of bytes. If every app wanted to work over files and let them be extendable, they would have to write and embed a whole-ass parser and compiler. There are 0 structural guarantees of the contents of the file. It's a lot easier to just create your own system that matches your domain model and work outside the filesystem entirely...which is why basically every app does so.

I want files on my computer to act as floors, not ceilings. I want apps to expose their capabilities as behavior that I can attach to my own files. Hopefully, I've created a convincing argument for it!

There are still a lot of questions though. I've been speaking in abstract terms, but I'd like to find the specific differences between each of these implementations (which I suppose will involve learning some type/category theory) and more (Java/Typescript interfaces, Haskell typeclasses). I'd also like to straddle the line b/w implicit and explicit extension, and see if there is a good middle ground. Finally, I hope to build a small prototype of an extendable system based on these ideas.